Quick Answer

Most private organizations cannot legally “take down” a drone with jamming, spoofing, hacking, or kinetic tools, even if the drone is over your site. In the U.S., only certain federal agencies have narrow, site-specific counter-UAS (C-UAS) authorities, and federal laws can still expose private operators to serious liability if they intercept communications or interfere with radio signals. In the U.K. and EU, radio interference and communications interception are also tightly restricted, and privacy laws apply to many detection setups. Always confirm with your aviation authority and get legal counsel before deploying any counter-drone tech.

Key takeaways

- “Detecting” a drone can be lawful, but how you detect matters (RF interception is higher risk than radar or camera).

- “Mitigating” a drone (disrupt, seize control, force it down) is usually restricted to authorized government actors.

- Jamming is broadly illegal for private entities in the U.S. and U.K., and commonly prohibited across Europe.

- Privacy and data rules still apply if you’re capturing identifiers, device data, or video of people.

- The safest path is usually preparedness + escalation, not “countering” the aircraft yourself.

Private Groups in Counter-UAS Operations

Counter-UAS (C-UAS) means capabilities to detect, track, identify, and potentially mitigate unmanned aircraft systems. “Mitigation” includes actions that disable, disrupt, seize, or destroy a drone.

Detection vs mitigation matters legally:

- Detection tools can include radar, electro-optical or infrared cameras (EO/IR), acoustic sensors, or RF (radio frequency) monitoring.

- Mitigation can include RF disruption (jamming/spoofing), cyber takeover, nets/projectiles, lasers, or other “force” options. These are the ones most likely to be restricted.

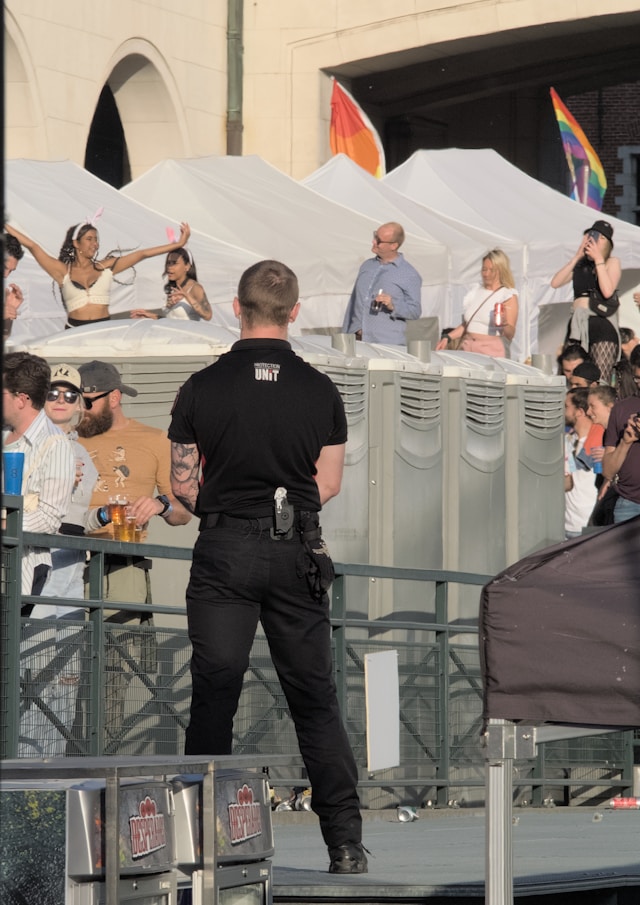

If you run security, facilities, or operations for a stadium, venue, festival, campus, hospital, hotel, data center, utility, industrial site, or even logistics hub, this guide is for you. It’s also relevant if you manage a corporate security team, oversee contracted guarding, or work in local government or a public agency that isn’t federally authorized for counter-UAS actions. And if you’re a drone operator, it matters too, because clients may ask you to “handle drones” on site. You only want to say “yes” to lawful actions.

Do not jam, spoof, hack, or physically strike a drone unless you have explicit legal authority. In the U.S. especially, federal law can treat interference with radio communications as illegal, and “taking control” or disabling an aircraft can trigger serious criminal exposure.

What Private Organizations Can Legally Do

These are common “yes, generally” actions (still confirm locally):

1. Strengthen site procedures without touching the drone

- Create a drone incident plan (who calls whom, what you document, when you pause operations)

- Improve access control and roof-line security to reduce launch points on your property

- Add signage and event briefings for drone prohibitions at venues (helps enforcement later)

2. Use low-risk detection that does not intercept communications

Radar, EO/IR, and acoustic systems are less likely to implicate U.S. federal criminal surveillance laws because they do not “capture, record, decode, or intercept” electronic communications.

That does not mean “anything goes” (you still have privacy duties), but it’s typically safer than tools that pull identifiers or decode links.

3. Collect evidence and escalate fast

- Record time, location, altitude estimate, direction of travel

- Capture non-invasive video for situational awareness

- Notify local law enforcement or event security command

- If near an airport or critical infrastructure, escalate per your aviation authority guidance

Restricted or High-risk Actions in 2026

U.S. restrictions

In America, a major guardrail is that Congress has granted limited counter-UAS authority to certain federal departments (not private entities), and the interagency legal advisory warns that state/local and private entities may be prevented, limited, or penalized for using many detection or mitigation capabilities.

Common legal tripwires include:

- Signal jamming or interference

Federal law prohibits willful or malicious interference with authorized radio communications (47 U.S.C. § 333), and the FCC warns jammers are prohibited.

- Intercepting communications

RF systems that capture device identifiers or communications can implicate U.S. surveillance statutes like the Pen/Trap statute (18 U.S.C. §§ 3121–3127) and the Wiretap Act (18 U.S.C. §§ 2510 et seq.).

- Hacking or “taking over” the drone

Tools that access or damage protected computers can implicate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (18 U.S.C. § 1030).

- Damaging, disabling, or seizing an aircraft

“Mitigation” actions can implicate aircraft-related criminal laws (e.g. 18 U.S.C. § 32 and 49 U.S.C. § 46502).

Yes, there are federal counter-UAS authorities (for example, DHS authority in 6 U.S.C. § 124n and DoD authority in 10 U.S.C. § 130i), but those are not a blanket permission for private organizations.

U.K. restrictions

- Deliberate interference is an offence

Under section 68 of the Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006, deliberate interference is illegal unless authorized. Ofcom also explicitly warns that RF jamming is unlawful without authorization.

- Interception and intrusive powers are controlled

The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 sets a framework for interception and equipment interference powers for public authorities, not private actors.

- Data capture rules apply

UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018 govern personal data use, which can include identifiable video or device-linked identifiers depending on your system.

EU and EASA region

At EU level, two big “always relevant” anchors are:

- GDPR for personal data processing.

- ePrivacy Directive (Directive 2002/58/EC) for privacy in electronic communications contexts.

EASA provides safety-focused material for drone incident management around aerodromes (useful for escalation planning), but enforcement and counter-UAS authorities still depend heavily on national law.

An example of national restrictions: in France, the spectrum regulator ANFR notes that possession and use of jammers are strictly prohibited except for tightly framed state derogations (with penalties referenced to national code provisions).

What to Do if You Want to Be Compliant

- Define your goal: awareness only, or active defeat? (Most private orgs should plan for awareness + escalation.)

- Choose lawful detection first: prioritize non-intercepting sensors and document exactly what data is collected.

- Run a privacy and legal review: confirm whether video, identifiers, or metadata are personal data under your regime.

- Write an incident plan: who calls police, who calls the aviation authority, when you stop operations.

- Train your team: most failures happen when someone “improvises” under pressure.

Do not buy “jammer” solutions without explicit authority and written legal clearance.

Common Mistakes That Create Legal Risk

- Assuming “it’s over my property” means you can disable it

- Trusting vendor claims without independent legal review (Do not rely on vendor representations)

- Deploying RF tools that quietly collect identifiers or intercept links

- Capturing lots of video without retention limits, signage, or a clear purpose

So identify your region and regulator (FAA and FCC, CAA and Ofcom, or national aviation and spectrum authorities in the EU). Confirm whether your detection captures communications or identifiers. Document your lawful basis for any data collection. Establish an escalation path and contact list. And train staff on “do not jam, spoof, hack, strike” rules

FAQs About Counter-UAS Actions with Private Security

Can a private security team jam a drone that is threatening a venue?

Usually no. In the U.S., jamming is generally prohibited for non-federal entities under federal law and FCC enforcement posture, and the U.K. prohibits deliberate interference unless authorized.

Is passive drone detection legal?

Often, but it depends on how it works. The U.S. advisory highlights that radar and EO/IR are less likely to implicate surveillance laws than RF interception, but you still must comply with communications and privacy requirements.

Can we “capture” a drone with a net or projectile?

That can create aircraft-damage and safety liabilities. Mitigation tools can implicate aircraft-related criminal laws. Treat this as “restricted unless authorized.”

Do privacy laws apply if we only film the drone?

They can, especially if people are identifiable or if data is retained and shared. GDPR and UK data protection law are your key anchors.

What should we do if drones keep showing up near an airport?

Use an incident plan and escalate quickly. For instance, EASA publishes aerodrome incident management material. Your national aviation authority and local law enforcement are typically the correct escalation path.

If you want see how specific states deal with drones and privacy, here are some reads: