In the UK today, truly free BVLOS flights don’t exist – any BVLOS operations must be authorised through the Specific Category with a safety case. The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has been actively updating rules and policies so that, in a few years, BVLOS flying can become routine.

CAA’s recent BVLOS Roadmap envisions that “the flying of drones beyond the visual line of sight…[will be] fully achieved in the next three years”. In other words, by 2027 you should be able to safely and legally fly drones BVLOS for many commercial applications.

Here, we’ll walk through the current rules and regs, CAA guidance, the 2027 BVLOS roadmap, required technologies (like detect-and-avoid and electronic conspicuity), real-world use cases and trials, airspace integration (including Temporary Reserved Areas and Atypical Air Environments), and finally what steps you – as a commercial operator – can take to prepare.

Understanding BVLOS And UK Rules Today

If you’re wondering “can I fly my drone beyond my line of sight?” – the short answer is: only with permission. Under UK law (retained EU rules), any BVLOS operation must be authorised in the Specific category.

The open category rules (for hobbyists and low-risk flights) do not allow BVLOS, except in very limited cases known as “extended Visual Line of Sight” (EVLOS). EVLOS means you keep your eyes on the drone indirectly using visual observers or aids, but even EVLOS flights must be authorised under the Specific category with a risk assessment.

The Specific category is where you handle higher-risk flights by applying to the CAA for an Operational Authorisation. This is now assessed using UK SORA (the UK Specific Operations Risk Assessment). New and renewal applications use UK SORA. Existing OSC-based authorisations remain valid until they expire, and you can still request variations on them until that date.

Since 23 April 2025, UK SORA is in force for Specific-category applications; OSC is legacy and valid only until its expiry.

For now, BVLOS flights are only allowed in controlled ways. Common approaches include flying in segregated airspace (e.g. a Danger Area), or in an Atypical Air Environment (AAE) where encountering manned aircraft is very unlikely (for example, close to tall infrastructure or in remote regions). If you fly in an AAE, the CAA notes that no formal airspace change is needed – because the risk is already mitigated by location. However, if you want to fly in normal airspace, you’ll need sophisticated safety measures.

Practically speaking, what BVLOS is allowed today? You can apply for Specific Category operations using the CAA’s current rules (e.g. CAP722, CAP722A, CAP3008). With CAA approval (and a good OSC), companies have done BVLOS flights for infrastructure inspection and medical delivery trials.

You’ll often see routes in segregated or temporary reserved areas with transponder requirements (TMZ/RMZ) so air traffic control can deconflict traffic.

The main point is: BVLOS is not “off the shelf” – you need CAA authorisation and risk mitigation.

CAA Guidance And Policies For BVLOS

The UK CAA publishes a range of guidance documents covering drone operations. Here are the key ones for BVLOS:

- CAP 722 (“UAS Operations in UK Airspace”) – This is the general drone policy manual. It defines BVLOS (beyond unaided visual line of sight) and explains that BVLOS flights in non-segregated airspace normally require an approved Detect-and-Avoid (DAA) system. CAP722 also clarifies EVLOS (using visual observers) can only happen under a Specific Category authorisation. CAP722 includes chapters on DAA and on Electronic Conspicuity (EC) – telling operators that UAS must be able to “detect and be detected” when flying BVLOS in shared airspace.

- CAP 722A (Operating Safety Cases) – This CAP is now a legacy reference for the OSC format. For new or renewal Specific-category applications, use UK SORA; CAP 722A mainly helps legacy OSC holders and variations until their authorisations expire. It used to be part of CAP722, but became standalone. The OSC covers your organization, equipment, procedures, training, etc.

- CAP 3008 (UK Guide to BVLOS in the Specific Category) – Released in July 2024, CAP3008 is a guide for industry about flying BVLOS in the Specific Category. It outlines six “operational pathways” for BVLOS (using danger areas, temporary segregated areas, TRAs with transponders, etc.) and lists what approvals and timelines each requires.Importantly, CAP3008 has since been overtaken by the introduction of UK SORA on 23 April 2025 for Specific-category applications. Where CAP3008 references ‘submit an OSC,’ read that as historical context; UK SORA is now the required method. CAA offers a pre-application service: If you email bvlos@caa.co.uk, the CAA will spend up to seven hours discussing your concept and advising on regulatory steps. CAP3008 also explains Atypical Air Environments (AAEs): these are places where crewed traffic is practically nil (e.g. close to tall infrastructure) and so BVLOS risk is low. In an AAE, you don’t need an airspace change, just demonstrate why mid-air collision risk is negligible.

- CAP 3182 (Future of Flight: BVLOS Roadmap) – Published in October 2025, this is the official CAA roadmap for BVLOS. It lays out the UK’s strategy to enable routine BVLOS operations by 2027. CAP3182 categorises use-cases into three levels: AAE (e.g. very low-risk corridors), Integrated Low-Level (urban/rural deliveries and inspections), and Fully Integrated (emergency services, offshore work, mid-distance logistics). It emphasises working with government and industry to evolve policies and technology step-by-step.

Sophie O’Sullivan, Director, Future, Safety & Innovation at the UK Civil Aviation Authority, notes the CAA is “working closely with innovators” and plans to “enable increasingly more BVLOS operations… to 2027 and beyond.”

- Other policy concepts and CAPs: The CAA has issued CAP2533 (“Airspace Policy Concept for BVLOS”) to describe how airspace structures will transition from segregated to integrated as BVLOS matures. CAP3145 (July 2025) defines a framework for Test Sites where companies can do flight trials in a controlled setting. CAP1391 is about Electronic Conspicuity devices if you use ADS-B/FLARM. There are also consultations like CAP2968 (on AAEs) and a wider Airspace Modernisation Strategy (AMS) which includes BVLOS. In summary, the CAA provides a clear path: use OSCs now, prepare for UK-specific SORA, and follow the emerging CAPs as they roll out.

The 2027 BVLOS Roadmap And Goals

Where is UK BVLOS headed? The CAA and Government have set a vision through the In CAP3182. At a high level, the goal is that within the next few years drones will be able to fly BVLOS “in all airspace classes… at levels of safety comparable to manned aviation” (the CAA’s long-term aim).

Key roadmap elements include:

- Routine BVLOS by 2027: The CAA states plainly that it has a plan to make BVLOS flights (for things like inspections and deliveries) a regular, accepted part of UK aviation by 2027. The roadmap is built on existing trials and technologies, scaled up safely. The CAA CEO notes these regulations will “unlock the full potential” of drones and are widely welcomed by industry.

- Incremental Pathways: Rather than one big leap, the roadmap lays out stages. We already touched on them in CAP3008: flying in Danger Areas, Temporary Danger Areas, Temporary Segregated Areas, or Temporary Reserved Areas (TRAs) with a transponder zone. CAP3182 bundles these into “accommodation phase” policies (like TRAs) that let BVLOS begin without full integration. By repeatedly conducting flights in these managed environments and proving DAA/EC technology, the CAA will gradually relax restrictions.

- Investment in Tech: The roadmap highlights Detect-and-Avoid and Electronic Conspicuity as critical technologies that must mature for BVLOS in normal airspace. In the near term, BVLOS will rely on these systems along with segregation. For example, the roadmap mentions that TRAs are likely to include mandatory ADS-B or FLARM requirements, so all aircraft inside can see each other. The CAA is also working on standards for UAS detect-and-avoid systems.

- Regulatory Milestones: Several specific targets are noted. For instance, UK SORA (Specific Operations Risk Assessment) – a formal, quantitative risk assessment framework – entered into force on 23 April 2025. Applications in the Specific category now follow the UK SORA method (rather than the older OSC approach). By 2026-27, the CAA expects to publish new airspace architecture (possibly under CAP3038 or related) that formalises how BVLOS flights fit into regular airspace.

- Use-Cases: The roadmap explicitly calls out priority use cases. These include NHS medical deliveries, emergency service support, infrastructure inspections (power lines, rail, wind farms), and commercial deliveries (shopping, mail, etc.). The idea is to solve real public benefits.

This means if you’re planning BVLOS flights, the next few years should progressively open more opportunities under a clear framework

Detect‑and‑Avoid and Electronic Conspicuity Today

One of the hottest topics for BVLOS is how drones will “see” and avoid other aircraft.

Under current UK policy (CAP722), BVLOS flights in non‑segregated airspace are not allowed unless the UAS has an approved Detect-and-Avoid (DAA) capability. CAA guidance points out that DAA is essentially a technical equivalent of the pilot’s “see and avoid” – it must detect other traffic (air and on-ground), obstacles, terrain, etc., and help the drone avoid collisions.

For now, because stronger DAA systems are still emerging, the CAA generally expects BVLOS flights to happen in segregated or special airspace (like Danger Areas or TRAs) where the risk of encountering other aircraft is controlled. In those zones, the rule-of-thumb is that the drone is free to operate without new surveillance if the airspace is well-managed. But outside those zones (true integration), the CAA has signaled that an “acceptable DAA capability” will be mandatory. In concrete terms, this might mean on-board radar or vision systems, or a combination of ground-based sensors that can detect non-cooperative aircraft and ensure separation.

Closely related is Electronic Conspicuity (EC). This refers to technologies like ADS-B, FLARM, or remote ID that allow aircraft to broadcast their position. The idea is that if all participants (manned and unmanned) have EC equipment, collisions are much less likely because everyone is “visible” electronically.

CAP722 UAS “must be able to ‘detect and be detected’ by means of available and recognised EC technology if operating BVLOS in non-segregated airspace”.

In fact, the UK is considering even mandating EC for drones. Practically, this means if you’re flying BVLOS, you should plan to equip your drone with an approved EC device (like ADS-B Out or FLARM transponder) so that other aircraft and air traffic control see you on radar or their screens. (By comparison, there is currently no legal requirement for remote ID in the Specific Category, but voluntary adoption is recommended.)

So the current state is: No BVLOS in uncontrolled airspace without safety help. CAP722 makes it clear BVLOS without some form of collision avoidance is not acceptable. Today’s typical BVLOS flights may use limited DAA (like a visual observer) or stick to segregated corridors. The future (and the regulator’s aim) is to develop certified DAA systems.

Many UK trials – including Project Skyway and others – are in fact testing DAA/EC solutions (radars, cameras, ADS-B networks) so that one day drones can blend into civilian airspace. The BVLOS roadmap notes that until DAA is proven, any integrated BVLOS ops will likely have extra requirements (e.g. mandatory ADS-B, or flying only in ANSP-managed TRAs).

Flying BVLOS will almost certainly mean equipping your drone with collision-sensing tech. If you want to fly in normal UK airspace (Class G, etc.), you’ll need an “approved DAA capability” – something at least as good as manned aviation’s see-and-avoid. And you should be prepared to use electronic conspicuity (EC) – think of it as your digital “tail light” that the CAA already strongly recommends for BVLOS.

BVLOS Use Cases And Trials in the UK

Several BVLOS projects and trials are already proving the concept. Let’s look at some examples, grouped by use case:

-

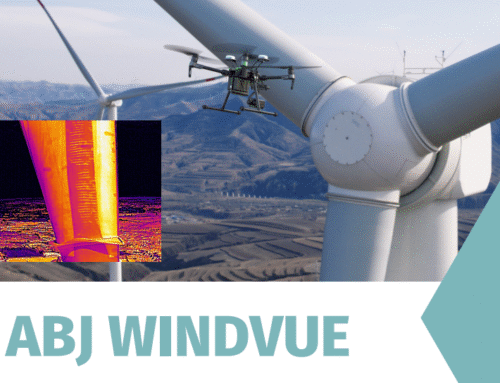

Infrastructure Inspection

Inspecting long assets (railways, power cables, wind turbines) is a natural fit for BVLOS. These kinds of projects often stretch for kilometres and require precision data capture across difficult terrain. While many UK operators are still trialling this capability, ABJ Drones already supports clients who need it by hiring certified BVLOS pilots as required. This allows the team to carry out complex inspections, whether that’s wind farm blades, telecom towers, or offshore platforms, with full compliance and high-resolution results. The company is ready to scale operations in markets like the UK as regulations evolve. By combining optical, thermal, and AI-assisted analytics, ABJ’s inspection workflow delivers actionable data from even the most remote sites, bridging the gap between field capture and decision-ready insights.

-

Medical and Emergency Deliveries

One of the most exciting early wins for BVLOS is medical logistics. In 2023 and 2024, UK teams ran BVLOS trials carrying blood and medical supplies. In Northumbria (Aug 2024), NHS Blood and Transplant and Apian ran the first UK BVLOS drone flights carrying 10 units of packed blood on a 68 km route between two hospitals. They compared flight vs road delivery and found drone transit was just as fast and safe for blood quality. (The CAA had authorised the airspace for this trial.) Separately, Scotland’s Project CAELUS (Care and Equity – Logistics UAS Scotland) flew lab samples BVLOS between Edinburgh and Melrose (Borders) in mid-2024, aiming to cut a road trip from 5 hours to 35 minutes. CAELUS is a UKRI/Future Flight consortium with NHS Scotland, NATS, University of Strathclyde, Skyports, etc. They’ve designed drone “landing stations” at hospitals and tested flights all around Scotland. These projects show that healthcare logistics will be one of BVLOS’s first beneficiaries.

-

Commercial Delivery

Beyond medicals, there’s interest in parcel and retail delivery. While still in early stages, trials are planned or happening. Project Skyway (below) fits here. (There’s also related work: For instance, the UK’s Drones for Medical Logistics project and private pilots like DPD/Archer exploring small-package delivery, though many remain in development.)

-

Drone Highways (Project Skyway)

Led by Altitude Angel with partners including BT, Skyway created a network of over 165 miles of “drone superhighway” sensor corridors across southern England. Ground-based cameras and RF sensors provide a unified air picture so drones using the corridor don’t need heavy on-board sensors. Trial flights began in July 2023 under existing permissions, with data feeding into CAA safety review. Skyway is a great example of using TRAs and ground sensors to enable BVLOS at scale. (BT even invested £5m in Altitude Angel for Skyway, and Guardian coverage hailed it as the “largest and longest network of its kind”.) While Skyway focused on technology development, it shows how commercial networks could serve last-mile delivery in the future.

Note: Drone Assist Provider Altitude Angel went into Administration on 7 October 2025.

-

Security Perimeter Patrol

Another use is site security (large campuses, borders, etc.). The CAA’s roadmap calls out “security inspections, such as perimeter inspections of large sites”. For example, airports and prisons could use drones to patrol fences by night. One UK startup has trialled BVLOS patrols at some industrial sites. (No high-profile news article here, but keep an eye on CAA sandbox trials – they’ve hinted at “industrial estate” trials in news.)

-

Offshore and Long-Range Flights

The UK is surrounded by offshore wind farms and oil platforms – ideal for BVLOS drones. While many trials still used small drones, one notable development is the first UK civil international BVLOS flight. In Sept 2025, Windracers (UK drone maker) received approval to fly a heavy-lift cargo drone from the Shetland Islands to Norway – a 235-mile cross-sea flight. They set up two temporary danger areas (UK and Norwegian) to create a safe corridor. Windracers’ ULTRA drone can carry 150 kg up to 600 miles, and this trial underlines how future BVLOS could support offshore energy (e.g. flying parts or medical supplies to platforms) and international routes.

Whether for public service (blood delivery), infrastructure maintenance (wind turbine surveys), or logistics, the current trend is: operators propose a clear mission, CAA authors an airspace plan (often a Danger Area or TRA), and the flight is carefully monitored (sometimes with chase planes or observers). The results so far have been promising. For instance, the NHS trials showed no degradation of blood quality from drone transi. Public surveys around these trials have generally shown strong support for medical BVLOS use (Project CAELUS reported “overwhelming public support”). It’s safe to say the UK is using real pilots in the loop to prove and improve BVLOS tech and rules.

Airspace Integration: AAEs, TRAs, and Segregated Zones

A big part of BVLOS is where in the airspace you can fly. The UK has created special frameworks to gradually integrate BVLOS:

-

Atypical Air Environments (AAEs)

As defined by the CAA, an AAE is a location where the chance of encountering other aircraft is negligible due to geography or infrastructure. For example, tight corridors near wind turbines or tall buildings, coastal areas beyond normal flight paths, or areas off busy routes can be considered AAEs. In these zones, the “air risk” (chance of mid-air collision) is very low. CAP3008 explains that if you operate in an AAE, you don’t need an airspace change – you just justify that it’s safe. This is one early way operators can do BVLOS without full DAA; it’s still a specific-category operation, but the CAA is more comfortable because traffic is minimal.

-

Temporary Reserved Areas (TRAs) and Temporary Segregated Areas (TSAs)

For more open-airline access, the CAA introduced the concept of TRAs (sometimes called sandboxes). A TRA is a temporary volume of airspace reserved for specific use (e.g. BVLOS trials), activated on demand. When a TRA is active, an ANSP manages it and may impose requirements (e.g. equipping with a transponder mandatory zone). Think of it as a “floating danger area” in busy airspace. CAP2533 (the Airspace Policy Concept) describes using TRAs alongside TSAs and danger areas to transition BVLOS from segregated to integrated flying. A TRA typically uses the existing airspace class (e.g. Class G) but with extra rules while active. CAP3008 notes that a TRA setup requires an airspace change (CAP 1616), and developing a new ANSP service if needed – which can stretch the approval to 8–12 months.

In practice, the UK has already used TRAs for trials. For example, the Windracers Shetland-Norway flight above went through a temporary danger area (a kind of semi-TRA) as a corridor. The CAA’s BVLOS policy describes TRAs as enabling “managed integration of BVLOS… with other airspace users” under agreed rules. Crucially, the CAA’s latest guidance states that electronic conspicuity will likely be essential for operations within TRAs – essentially pre-placing the need for ADS-B/FLARM there. And to actually run a TRA, the operator must show an Air Navigation Service Provider (ANSP) can manage it; CAP3008 says you may need to set up a new ANSP service or equip one, often under a “GEN03 trial” designation. This is complex, but it’s the path to proving BVLOS in shared airspace.

-

Segregated Airspace (Danger Areas)

A classic way to do BVLOS safely is in segregated airspace – e.g. military danger areas, or civil danger areas. Many UK BVLOS ops have flown in designated Danger Areas, where non-participating traffic is kept out. CAP3008 includes “Existing Danger Area in uncontrolled airspace” as one approved pathway. If the danger area already exists, you submit a safety case referencing its procedures. This route can take as little as 2–4 months for approval, since no airspace change is needed. The downside is it’s limited (only some areas can be used) and you might need to load nearby militias, but it’s a proven method (e.g. some power-line inspections fly in this way).

All these integration methods show a careful integration: start with extreme caution (segregated zones, visual observers) and gradually introduce tools (EC, DAA) until flights can enter normal airspace. The CAA’s BVLOS roadmap and AMS are lining up these pieces. For example, CAP2533 (April 2023) calls out transitioning from “segregated BVLOS operations” through a phased approach toward “integrated, unsegregated operations”. The policy even notes that DAA and EC developments, along with data from these pilots, will signal the move from “accommodation” (TRAs, TSAs) to full integration.

As an operator, this means your BVLOS plan may initially rely on one of these special environments. You might use an AAE if available, or negotiate with an ANSP to activate a TRA/TSM/Z or join a CAA sandbox trial. The CAA has been running sandbox trials where they work with consortia (like Project Skyway or others) to test these new concepts.

Taking UK BVLOS From Hurdles To Real-World Wins

Flying BVLOS safely is hard. But it also offers huge benefits if done right. Here are some of the main challenges and opportunities for UK operators:

- Regulatory Complexity: Right now, BVLOS flights require detailed applications, risk assessments (OSCs or soon SORA), and possibly airspace changes. That’s a lot of paperwork and planning. You must demonstrate safety with data or models for every new route. On the flip side, the CAA is being proactive – they offer free help sessions (as mentioned) and are consulting on new rules. The key opportunity is to engage early. Many operators find that aligning with CAP3008’s “operational pathways” and using the CAA’s advice can smooth the process. And with the 2027 roadmap, the aim is that by year-end, a known framework will be in place.

- Technology Maturity: Detect-and-avoid systems for small drones are still maturing. Cameras, radar, ADS-B (which wasn’t built into small drones originally) – integrating all this reliably, at scale, is engineering-intensive. Communication links (control and data) must also be rock-solid. However, several UK companies are innovating here (e.g. drone makers integrating onboard radar, or ground-based sensor networks like Skyway). Electronic conspicuity devices are already available (ADS-B Out trackers, etc.), and the CAA has CAP1391 to list approved devices. The opportunity is that in the next few years, off-the-shelf DAA and EC packages will emerge, making it easier for you. Meanwhile, you can start by equipping your UAS with the best available ADS-B or 1090 MHz device to show compliance.

- Airspace Access: Integrating drones with normal air traffic remains a hurdle. For example, UK airspace is busy near London and other cities. Getting permission to fly BVLOS there means coordinating with many stakeholders (ANSPs, military, local glider clubs). The introduction of TRAs and rulesets is meant to help, but it can still be a slow process. The positive side is the UK is actively reforming. The AMS and new CAPs aim to provide clearer corridors. Once systems are proven (e.g. robust DAA, proven ATM data links), the hope is that ATC will treat drones more like regular VFR traffic. Your opportunity is to participate in this evolution: by providing your test data and flight reports, you help shape how fast integration happens.

- Insurance and Public Acceptance: Flying BVLOS over people or property raises liability questions. If something goes wrong out of line-of-sight, who is at fault? Operators are working with insurers to cover these operations. On the public side, surveys in the UK have generally shown support for useful drone services – especially for health and safety use cases. The reassurance from these first trials (blood delivery without issue, for example) helps build confidence. Your role here is to maintain transparency: coordinate with local communities, publish safety results, and stick to noise/no-privacy limits (UAS.SPEC.050 noise caps). The opportunity is huge social benefit (faster medicine, greener delivery, more affordable infrastructure checks) which usually translates to political support.

- Training and Skills: BVLOS will require pilots and support crew to have advanced training. With UK SORA, expect new training standards for Specific operations. Fortunately, the CAA has signposted new Remote Pilot Competency regulations on the way. You should anticipate taking formal courses in risk assessment and UAS operation. The opportunity is to upskill and certify your team early, so you’re ready when full BVLOS permission opens up.

- Innovation Support: The UK government and regulators are keen on drones. That means grants, trials and innovation programs are available (we’ve seen Future Flight Challenge funds, R&D tax credits, etc.). Operators can tap into those to develop BVLOS tech or participate in consortia (like we saw with Skyway and CAELUS). So an opportunity is to piggyback on government/industry partnerships and demonstration projects, which can fast-track your learning and approvals.

Getting BVLOS-ready means tackling technical and procedural challenges, but the carrot is big – the CAA envisions a UK where drones make railways safer, supply hospitals quickly, and deliver goods without burning road fuel. The industry is ready to move faster on low-risk flights and the CAA want collaborative progress.

Next Steps For Operators

So, you’re excited about BVLOS. What should you do tomorrow? Here are some practical steps to consider:

- Stay Informed and Plan Early: Keep an eye on CAA updates. The CAA has policy pages (like the BVLOS and SORA pages we cited) and regularly updates CAPs. Subscribing to CAA newsletters or following drone industry groups (like ARPAS UK) can help. Plan your BVLOS concept now – even if you won’t fly for a few months, start drafting your Concept of Operations (ConOps).

- Contact the CAA BVLOS Team: Take advantage of the free CAA support. Email bvlos@caa.co.uk early with a summary of your proposed flight (location, purpose, aircraft type). The CAA will allocate experts to review it. According to CAP3008, this free consultation can provide up to seven hours of advice on your best pathway. It saves time later. You’ll likely discuss whether your idea fits an existing Danger Area, AAE, or needs a new airspace change. They can flag issues (e.g. if an ANSP needs to get involved).This step significantly reduces delays when done up front.

- Prepare Your UK SORA Assessment: Work on a thorough UK SORA assessment now. Document your aircraft, operational procedures, pilot competency, maintenance, C2 link resilience, contingency and recovery plans, ground-risk mitigations, and any strategic or tactical mitigations. You might consider getting SORA training – some providers are developing courses now.

- Equip for Detect-and-Avoid: Outfit your drone with any available detect/avoid gear you can. At minimum, fit an Electronic Conspicuity device that’s CAA-approved (ADS-B or FLARM). Register it properly: as CAP722 advises, after buying an EC device you must email NISC at CAA to get a unique ICAO hex address. For DAA, if your drone has any onboard camera or radar, make sure it’s calibrated and you have procedures to use it for collision avoidance. As a future-proofing step, consider participating in trials of new DAA systems (some companies offer to test your aircraft).

- Engage with Airspace Control: Depending on your flight path, you’ll work with an Air Navigation Service Provider. If you fly in controlled airspace or near an airport, talk to the relevant ATC unit early (CAA can help with contacts). They may require you equip a Mode S transponder code (e.g. 7400 for lost C2 links) or route you through TMAs. If your plan needs a new TRA/TSA, begin the Airspace Change Proposal (ACP) process via CAP1616. The CAA site has guidance on ACP and CAP2989 as it relates to drones.

- Collaborate and Learn from Trials: Look for opportunities to join consortiums or trials. Projects like Skyway and CAELUS had formal consortia; others might have open invitations. Even if you run solo, you can learn from published trial results. For example, read the NHS/Apian trial report (NHSBT website) and NATS’s reports on CAELUS. These often share safety metrics and lessons. The CAA encourages shared learning, so participating in industry forums can give you an edge.

- Build Industry Partnerships: Operators often succeed by teaming with UTM (drone traffic management) providers and ANSPs. Technologies like UTM platforms (altitudeangel, uAvionix, etc.) can help file flight plans and exchange separation data. An example is using the Common Information Service (CIS) to share intent with other airspace users. Even if not mandatory yet, adopting these tools aligns with where things are headed.

- Prepare for Certification and Markings: While not specific to BVLOS, keep in mind future regulatory changes: from 2023 onwards, UK requires drones to have class markings (like C0, C1, etc.) and potential UKCA/CE certification. By 2024-25, a new “SAIL” mark (Specific Assurance and Integrity Level) for Specific Ops might be introduced. It’s wise to follow the CAA’s policies on Flightworthiness and Class Marking. Having a recognized SAIL mark on your UAS (or getting SDoC / EC marking) will streamline the approval process.

- Address Uninvolved People and Safety: Plan how you will protect anyone on the ground. The UAS regulations emphasize not endangering “uninvolved persons”. For BVLOS, this means careful risk modelling (overflights of populated areas will get extra scrutiny). Have mitigation plans like deploying spotters, doing flights at safe altitudes, using parachute recovery kits, etc. The public and ATC care about that. Demonstrating sound ground risk management will be critical in your application.

- Stay Flexible and Adaptive: Finally, be prepared to adapt your plan as new rules roll out. The CAA’s note in CAP3182 that they will iterate policies means the regulatory environment will keep evolving. Keep lines open with regulators, and be ready to update your procedures. The upside is that the CAA wants industry input and is actively seeking feedback on these drafts. Your input can shape the final rules, so if something seems too burdensome or unsafe, let the CAA know.

By engaging early, using the CAA’s guidance, equipping appropriately, and learning from current trials – you’ll be well-positioned to fly BVLOS under the new rules as they come into force. Remember, the goal of all this is to unlock new capabilities: not just to go far from the pilot’s sight for its own sake, but to enable practical services (fast deliveries, better surveys, emergency aid) that benefit everyone. With the right preparation, you can be at the front of this new era of aviation.

FAQs About BVLOS Drone Flights in the UK

What does BVLOS mean?

It means flying a drone beyond the pilot’s unaided visual line of sight. In the UK that’s only allowed under the “Specific” category with formal authorisation; truly “free” BVLOS isn’t a thing yet.

Can I fly BVLOS in the UK today?

Yes, but only with CAA approval in the Specific category and a solid safety case. Most approvals lean on segregated or specially managed airspace, or very low-risk locations.

What’s the difference between BVLOS and EVLOS?

EVLOS keeps the aircraft effectively “in sight” via observers or aids, while BVLOS is truly beyond view. EVLOS still needs Specific category authorisation; it isn’t allowed in the Open category.

Which CAA documents matter for BVLOS?

Start with CAP722 (general rules), the UK SORA guidance for Specific-category applications, CAP3008 (BVLOS in the Specific category), and the BVLOS roadmap (CAP3182). Together they explain today’s pathways and the plan to make BVLOS routine by 2027. (CAP722A ‘OSC’ is now legacy—use UK SORA for new and renewal applications.)

Is the CAA really aiming for routine BVLOS by 2027?

Yes— that’s the stated goal in the BVLOS roadmap. The approach is step-by-step: start in managed/segregated environments, mature tech like detect-and-avoid (DAA) and electronic conspicuity (EC), then open up wider airspace access.

What do I need to apply for right now?

An Operational Authorisation in the Specific category assessed using UK SORA. The OSC lays out your aircraft, crew, procedures, risks, mitigations, and how you’ll keep people and other airspace users safe.

I’ve heard about SORA—when does that matter?

It matters now—UK SORA is the required method for Specific-category applications as of 23 April 2025, replacing the old Operating Safety Case (CAP 722A “OSC”). If you already hold an OSC-based authorisation, it stays valid until it expires, and you can still request variations on it until that date. New or renewed applications now go through the UK SORA process via the CAA’s digital service.

What airspace options do operators actually use for BVLOS?

Common routes are: existing Danger Areas, Temporary Reserved/Segregated Areas (TRAs/TSAs), and very low-risk Atypical Air Environments (AAEs). Each path has different lead-times, stakeholders, and equipment expectations.

What’s an Atypical Air Environment (AAE) in simple terms?

It’s a place where encountering crewed aircraft is extremely unlikely, so the mid-air collision risk is already very low. Think close to tall infrastructure or remote corridors; you still need Specific-category approval, but no formal airspace change.

How are TRAs different from Danger Areas?

TRAs are temporary, on-demand “reserved” volumes managed by an ANSP, while Danger Areas are segregated airspace where non-participants are kept out. TRAs often include extra rules (like mandatory transponders/EC) and usually need an Airspace Change Proposal.

Do I need Detect-and-Avoid (DAA) to fly in normal (non-segregated) airspace?

Yes—without an acceptable DAA capability, BVLOS in non-segregated airspace isn’t permitted. That’s why many missions currently stick to segregated/managed airspace while DAA tech matures.

What is Electronic Conspicuity (EC) and do I need it?

EC makes you electronically visible (e.g., ADS-B or FLARM), and you should plan to use it for BVLOS. The CAA stresses “detect and be detected,” and TRAs are likely to require EC for all participants.

Are there real UK examples of BVLOS in action?

Yes—several. Recent trials include NHS medical deliveries (e.g., blood and lab samples), long-asset inspections, “drone highway” corridors (Project Skyway), and an approved Shetland-to-Norway cargo corridor by Windracers.

What did the NHS trials actually prove?

They showed BVLOS can move critical medical items as fast as by road without harming quality. These CAA-authorised flights give regulators and the public confidence in safety and usefulness.

How long do approvals take?

It depends on the pathway. Reusing an existing Danger Area can be relatively quick (a few months), but creating and staffing a TRA with an ANSP and doing an airspace change can take longer (often many months).

Does the CAA offer any hands-on help?

Yes—the CAA runs a free pre-application service for BVLOS concepts. You can email the BVLOS team to discuss routes, airspace options, and requirements before you submit, which often saves time later.

What should my aircraft be equipped with for BVLOS?

At minimum, plan for EC and robust comms; add DAA where required by your airspace and concept. Document everything in your OSC/SORA, including maintenance, C2 link resilience, contingency, and recovery procedures (e.g., parachutes).

How do I manage risk to people on the ground?

Model it early and layer mitigations. Typical measures include careful route design, altitude management, safe-drop systems, spotters for critical segments, and clear abort/contingency procedures—spelled out in your safety case.

What skills and training will my team need?

Expect higher competency standards for BVLOS. The CAA signals new competency frameworks alongside SORA; invest in training for risk assessment, BVLOS procedures, and your chosen airspace pathway.

What are the biggest blockers right now?

Regulatory complexity, maturing DAA tech, and airspace access remain the hurdles. The roadmap addresses these with staged integration (AAEs, TRAs), standards for DAA/EC, and updated guidance.

I’m planning a BVLOS project—what are my first three steps?

Define your concept, contact the CAA BVLOS team early, and start drafting your OSC/SORA. In parallel, pick your airspace pathway (AAE, existing Danger Area, or TRA), line up ANSP engagement if needed, and spec your EC/DAA equipment.

How does this all translate to real business value?

BVLOS lets you cover long, hard-to-reach assets and time-critical logistics more efficiently. That’s why early use-cases include power lines, rail, wind, offshore support, and NHS deliveries—areas where distance and time matter most.